Gianni Berengo Gardin, Mario Giacomelli, Mario De Biasi, Franco Pinna, Pepi Merisio, Enzo Sellerio, Alfredo Camisa, Carlo Bevilacqua, Piergiorgio Branzi, et al.

The Sacred

December 13th, 2014 - January 30th, 2015

Franco Pinna, San Fele. Santuario della Madonna di Pierno, 1956

Franco Pinna, San Fele. Santuario della Madonna di Pierno, 1956

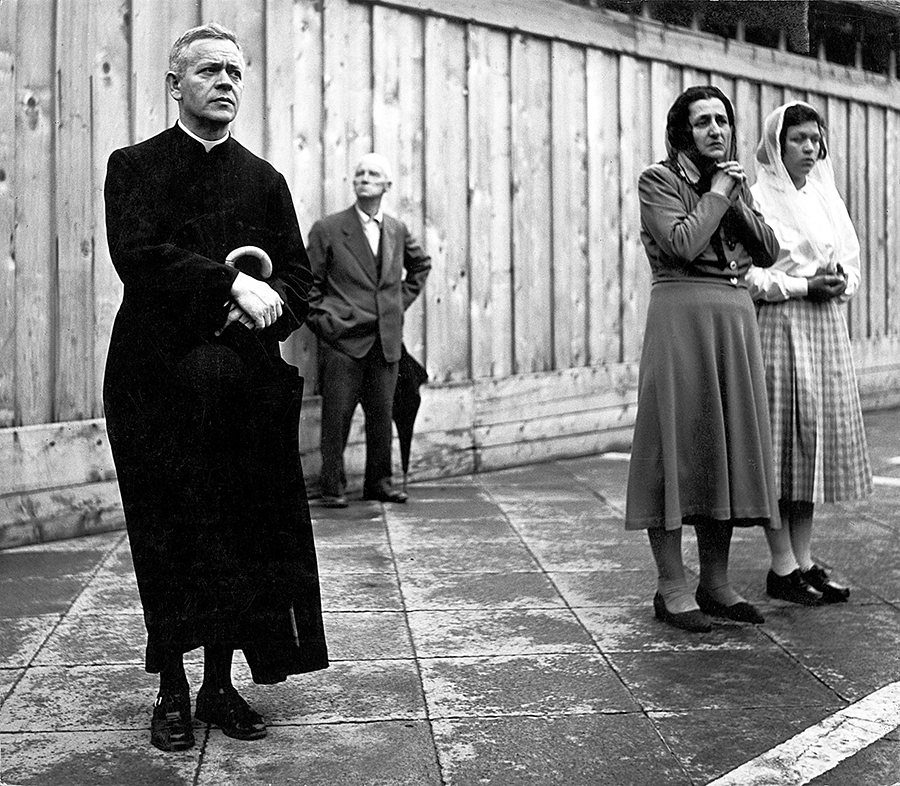

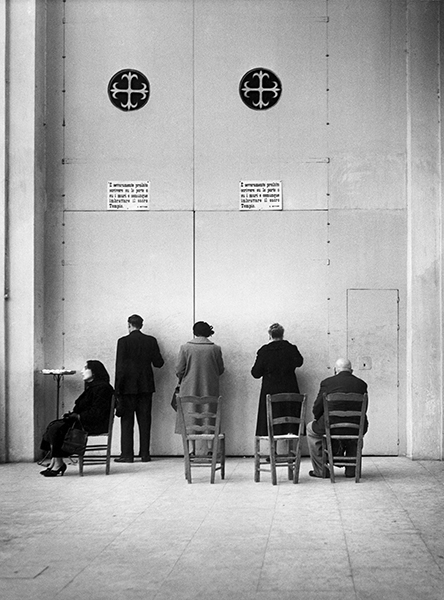

Gianni Berengo Gardin, Venezia. Corpus Domini, 1957

Gianni Berengo Gardin, Venezia. Corpus Domini, 1957

Gianni Berengo Gardin, Venezia. Corpus Domini, 1957

Gianni Berengo Gardin, Venezia. Corpus Domini, 1957

Pepi Merisio, Pellegrini al santuario di Caravaggio, 1956

Pepi Merisio, Pellegrini al santuario di Caravaggio, 1956

Enzo Sellerio, Trecastagni. Festa dei Santi Alfio, Cirino e Filadelfo, 1963

Enzo Sellerio, Trecastagni. Festa dei Santi Alfio, Cirino e Filadelfo, 1963

Mario Finocchiaro, Sant'Alfio, 1958

Mario Finocchiaro, Sant'Alfio, 1958

Mario Finocchiaro, Sant'Alfio, 1958

Mario Finocchiaro, Sant'Alfio, 1958

Mario Garrubba, Mosca, 1964

Mario Garrubba, Mosca, 1964

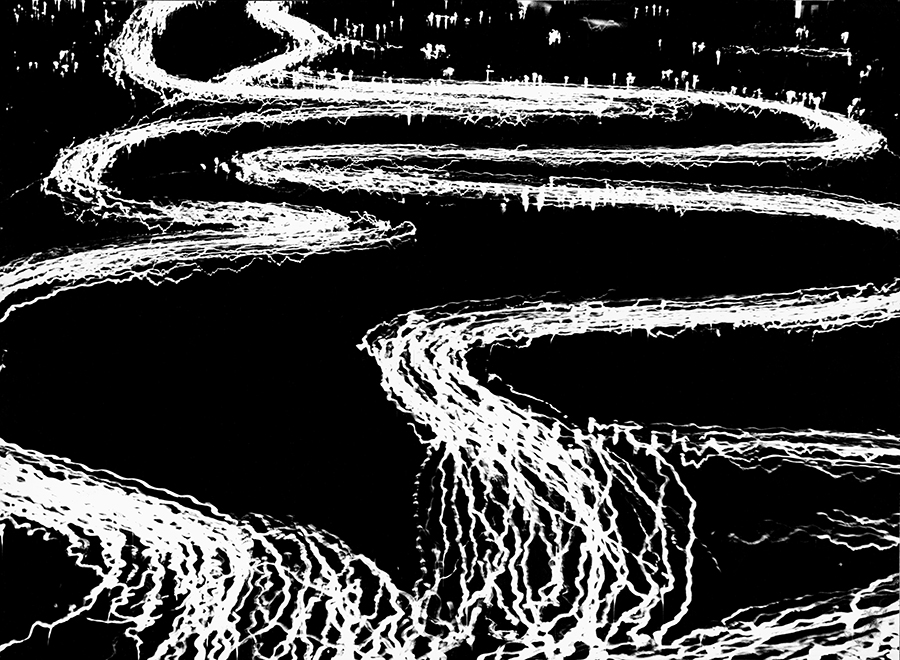

Mario Giacomelli, Lourdes, 1957-59

Mario Giacomelli, Lourdes, 1957-59

Mario Giacomelli, Lourdes, 1957-59

Mario Giacomelli, Lourdes, 1957-59

Mario Giacomelli, Lourdes, 1957-59

Mario Giacomelli, Lourdes, 1957-59

Mario Giacomelli, Vita d'ospizio, 1955 c.

Mario Giacomelli, Vita d'ospizio, 1955 c.

Carlo Bevilacqua, Processione, 1957 c.

Carlo Bevilacqua, Processione, 1957 c.

Piergiorgio Branzi, Firenze. Vicolo de' Donati, 1956

Piergiorgio Branzi, Firenze. Vicolo de' Donati, 1956

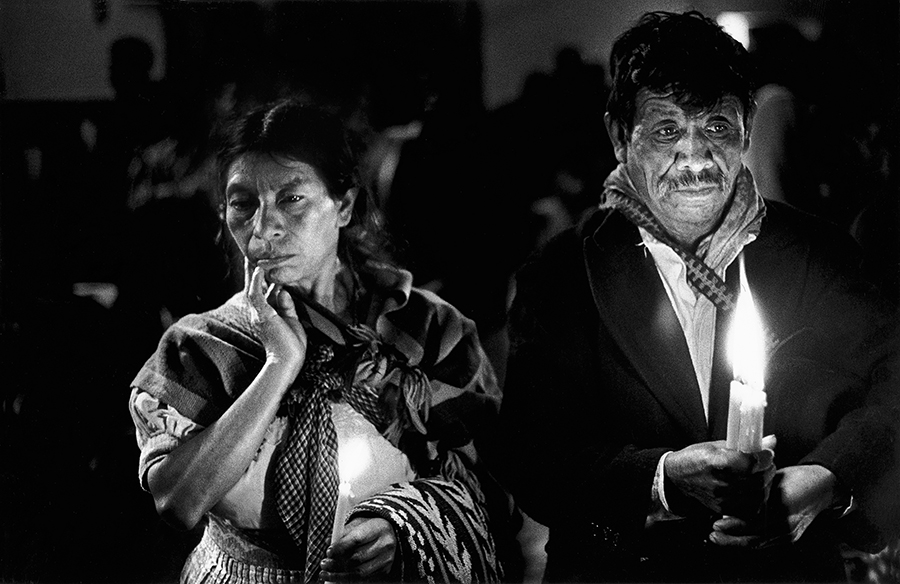

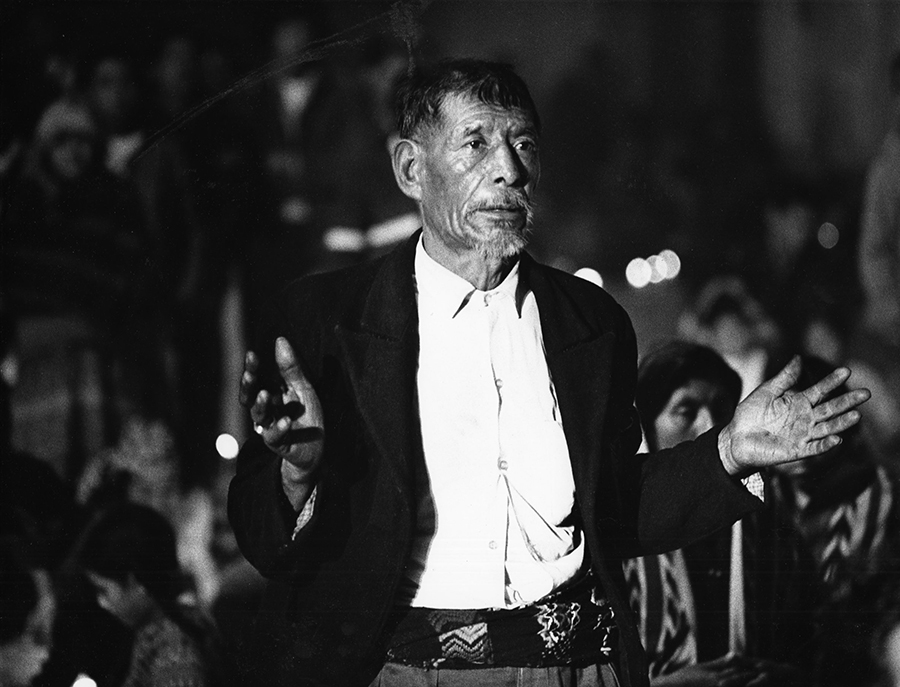

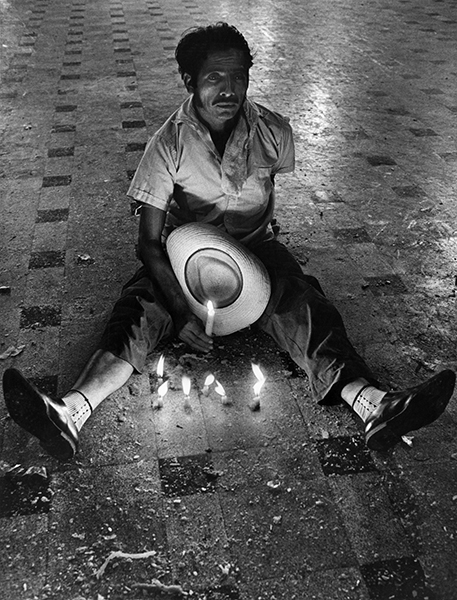

Mario De Biasi, Guatemala. Festa di san Tomas a Chichicastenango, 1972

Mario De Biasi, Guatemala. Festa di san Tomas a Chichicastenango, 1972

Mario De Biasi, Guatemala. Festa di san Tomas a Chichicastenango, 1972

Mario De Biasi, Guatemala. Festa di san Tomas a Chichicastenango, 1972

Mario De Biasi, Guatemala. Festa di san Tomas a Chichicastenango, 1972

Mario De Biasi, Guatemala. Festa di san Tomas a Chichicastenango, 1972

Alfredo Camisa, Cordoba. Settimana Santa, 1959

Alfredo Camisa, Cordoba. Settimana Santa, 1959

Pepi Merisio, Pellegrinaggio al Monte Autore, 1966

Pepi Merisio, Pellegrinaggio al Monte Autore, 1966

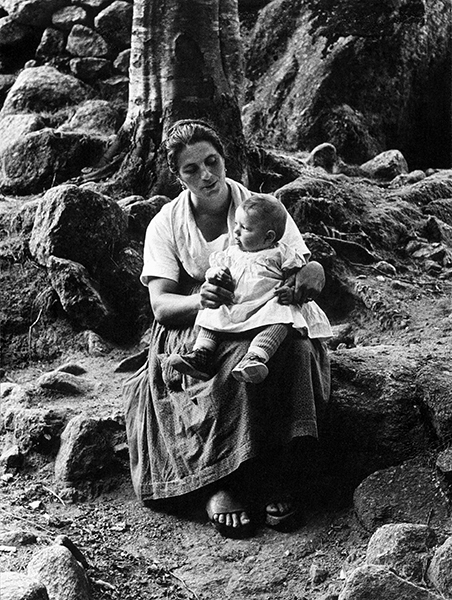

Pepi Merisio, Valle di Mello (Sondrio), 1962

Pepi Merisio, Valle di Mello (Sondrio), 1962

Carlo Bevilacqua, Mesto ritorno, 1957 c.

Carlo Bevilacqua, Mesto ritorno, 1957 c.

Mario De Biasi, Babilonia, 1956

Mario De Biasi, Babilonia, 1956

Franco Pinna, Ferrandina. Processione contro la bestemmia, 1956 c.

Franco Pinna, Ferrandina. Processione contro la bestemmia, 1956 c.

Enzo Sellerio, Palermo. Nella chiesa di San Domenico, 1953

Enzo Sellerio, Palermo. Nella chiesa di San Domenico, 1953

Piergiorgio Branzi, Ischia. Muro bianco, 1953

Piergiorgio Branzi, Ischia. Muro bianco, 1953

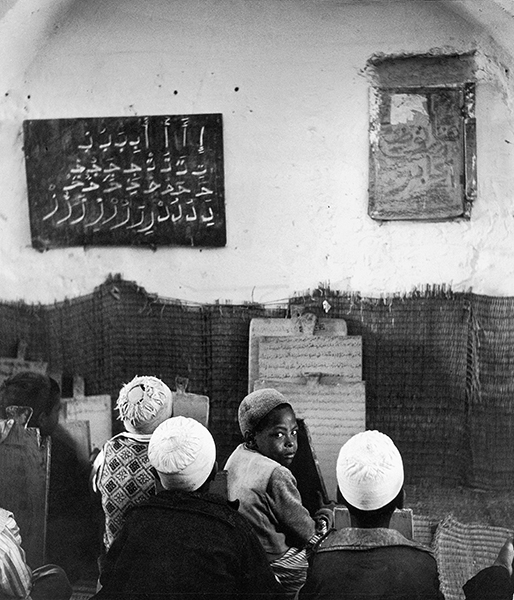

Alfredo Camisa, Scuola coranica, 1956

Alfredo Camisa, Scuola coranica, 1956

Popular religiousness was a topic of the highest interest in XXth century photography. Often working alongside writers and etno-anthropologists, reporters put a great deal of effort into documenting feasts and rites all around the world, and into representing the multifaceted nature of devotion with its gray edges between true belief and superstition. An extraordinary series of vintage prints taken by Italian photographers from the second World War period onward are on display until January 30th, 2015 at the Paolo Morello Studio Gallery in Palermo, Italy. The show starts from ‘Italia magica’ (Magical Italy), a series of reportages by Federico Patellani, published in 1952 in ten instalments on the magazine ‘Tempo’. A free-lance photographer, Patellani undertook a journey to Southern Italy to throw light on the magic rites still extremely popular at that time. In the same year, noted etno-anthropologist Ernesto de Martino organized his first ‘scientific expedition’ to Lucania to research on the survival of pagan rites and, particularly, of funeral laments in contemporary societies. A team of scholars, cameramen and photographers travelled with him, among them Arturo Zavattini, Ando Gilardi and Franco Pinna, whose pictures were to be used later on to illustrate de Martino’s groundbreaking books. A few years later, in 1956, Pepi Merisio took a touching series of pictures devoted to the ill people praying at the Caravaggio sanctuary, near Milan. The same did Mario Giacomelli in Lourdes, in 1957 and again in 1959, depicting human suffering as nobody else before him had done. Both Merisio and Giacomelli felt personally much involved in their subjects’ anguish: they were proud to state they were there not just to witness, but to share with those suffering people their pains. Feeling involved is a matter of personal sensibility. It is a matter of fact, nevertheless, that even those photographers who admittedly looked at religion with skepticism could not approach these situations without an emotional involvement. Caio Mario Garrubba was a member of the Communist party, and as a photographer he used to travel to Russia on official assignments. Yet the picture he took in Moscow in 1964 in an orthodox church is moving: the old lady with her eyes closed, one hand on her heart, is a telling icon of the meaning that religion had in Soviet Union. The exhibition reaches its climax in two extremely rare vintage prints by Gianni Berengo Gardin, both taken in Venice in 1957 at the Corpus Domini procession. The psycological intensity of the people portrayed here is unrivalled. Renowned for his witty anticlerical pictures which regularly appeared on ‘Il Mondo’, Berengo Gardin shows here his sympathy toward any expression of human beings. When representing the Sacrum, photographers’ points of view seem to be overwhelmed with a sense of respect. Would they represent christian, muslim, buddhist or jewish rites, they always seem to be stricken by the candour of the circumstance. To represent the Sacrum hid an unexpected challenge for all of those photographers who were engaged in the struggle for realism: nothing is more real, powerful, and actual than a religious belief, yet nothing is more abstract, ineffable, purely mental. So, how to represent in realistic terms the most ineffable feeling? Popular religiousness is always a mix of love and fear, hope and expectations, dogmas and compromises. Mario De Biasi gave a great synthesis of all that in a gorgeous series taken in Chichicastenango, Guatemala, at the feast of St Thomas, in 1972. Under the light of dozens of candles, the believers offer the viewer their fragility, taking part to the rite as the shepherds in a living nativity.